Tracy Rolstad

It is clear from ERCOT’s presentations that a notable amount of generation was unable to perform during the cold snap in Texas. It is also important to understand that ERCOT’s load shedding did what it needed to preserve the Texas interconnection. ERCOT deserves credit for making some tough choices under challenging conditions.

‘Cold’ is a relative term

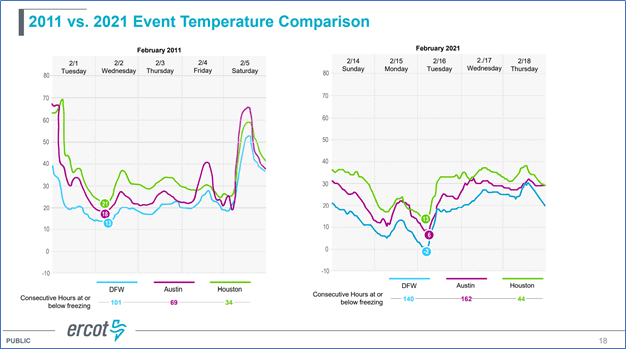

ERCOT’s reporting shows how unseasonably cold it was in Texas. Was it really that cold? Well, yes…for Texas. Folks in Wyoming or Minnesota might have considered it a few mild winter days.

So, what happened? Summed up in a word, it was about winterization, or lack thereof. I won’t get into any of the issues about capacity markets, regulation, energy-only markets, flawed markets, etc., in this post. What I will say is that the hallmark of professionalism in the utility business is as follows:

“To be boring and taken for granted.”

An exciting day at a utility is generally a bad day especially when loss of load service is involved.

Standards for extreme event planning

Alright then, what sort of standards might be out there that could be relevant in preventing this type of thing from occurring again? Presently, there are no NERC mandatory reliability standards that directly speak to generation availability under adverse weather conditions. It is probably fair to say that we should expect a draft standard shortly. Indeed, NERC does have a body of work in process regarding cold-weather performance. Not surprisingly, the “Project 2019-06 Cold Weather” effort is pretty busy right now.

There is a standard that does broadly touch on this kind of event, though. TPL-001-5 Transmission System Planning Performance Requirements speak to extreme event planning (see Table 1 of the TPL-001-5 standard). Table 1 indicates that “Wide area events affecting the Transmission System based on System topology such as: severe weather, e.g. hurricanes, tornadoes, etc.” should be evaluated. Additionally, Table 1 indicates that wide area events include “other events based upon operating experience that may result in wide area disturbances.”

Bias for action is needed

Cold weather outages did happen widely in Texas in 2011, so why did they happen again ten years later? Didn’t folks in Texas “plan” for cold weather occurrences again?

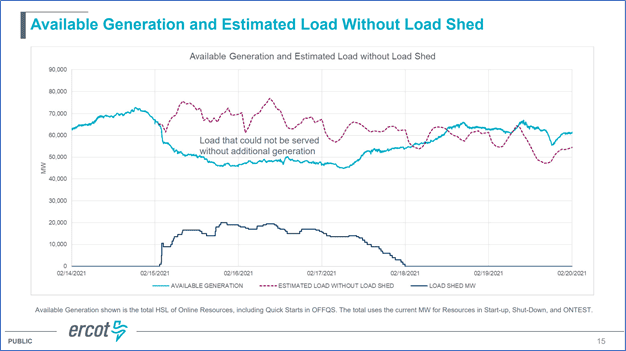

All signs indicate they did have plans for cold weather events, but those plans clearly did not prevent what happened in February 2021. How did things go awry? We can see below that the operational plan for committed generation vs. load forecast was sound. Reserves were available at around 9%. Reserves around 9% is a reasonable amount, if maybe a bit on the modest side given the 2011 winter storm in Texas.

All roads lead back to the NERC implementation of mandatory reliability standards from the Energy Policy Act of 2005. The NERC standards are written by the industry itself, which is not, in and of itself, either a good or bad thing. What does rise from this method, however, is a lowest common denominator sort of thinking. To get a standard to pass (absent FERC intervention) requires a majority vote of the relevant NERC membership. If a standard requires notable (i.e., costly or expensive) action from a utility, one might reasonably expect the votes to be hard to come by.

What we have seen in the NERC standards is much language about plans, but none about executing the plan on a specific schedule. In fact, in the TPL-001-5 standard there are no instances of the words execute, build, or construct.

Perhaps it is time for the various NERC standards to have more actionable language about actually deploying capital per planning study results.

Evaluating risk is critical

Finally, we do think the engineering profession is generally short of the mark in evaluating risk. Risk is often defined as follows:

Risk = Probability * Consequences

A brief review of what might be termed as engineering failures (really planning failures) is in order:

- Hurricane Katrina impacts

- Hurricane Sandy impacts

- Northeast Blackout of 2003

- Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster

These events have one relevant thing in common: the impacts were all preventable or could have been readily mitigated.

So what happened? One issue is a remarkable reticence to study extreme events and then document the findings. This is probably due to the sense of the probabilities being too low, and the idea that if you write it down you will have to do something about it. The idea of a 1 in 100 probability has been viewed as generally acceptable despite the consequences (or perhaps the consequences were never fully explored). Today, a greater appreication needs to be given to consequences and a recognition needs to be paid to 1 in 100 probabilities as being too likely. We have harnessed electricity for over 100 years, so it might be time to use a 1 in 1000 probability. Another way to look at it might be to truly appreciate the direct and indirect consequences that compose risk. Given the continued fallout in Texas (bankruptcies, legislative action, employment termination, legal action, etc.) it is fair to say everyone in Texas wants a do-over on the 2021 cold snap.

Study hard, study often

What should electricity planners do about something like this? Study hard and study often. Have an open mind about extreme events. Document your study results and develop a plan for the worst case. And, then when the 1-in-100 does happen, execute the plan or explain why you have chosen not to execute it.